Manufactured Migration

On migration forced by foreign policy, race and asylum, and an ecosystem of surveillance, patrolling, and job creation at the border.

There is a lot of weird language used around the US migration process — describing asylum seekers as an assault on American security is just as common as describing seeking asylum as “in the name of asylum”.

One insinuates a right, the other insinuates a lie. Today we have an expert on immigration enforcement answer some burning questions, like, how does one literally claim asylum? Who determines whether that claim is valid? And much more.

This interview with Austin Kocher, assistant professor at Syracuse University who focuses on the political and legal geographies of immigration enforcement, policing and the immigration court system, was conducted and condensed by Tatti Ribeiro for franknews. You can subscribe to Austin’s Substack here.

Can you explain how asylum works – generally speaking?

The immigration system is a very dynamic policy space, which is to say, how it works at one point in time can be quite different from another point in time. The border is the focus of a lot of immigration enforcement activity, but 10 years ago, during the Obama and Trump administrations, interior enforcement – where ICE is raiding workforces and taking custody of people arrested by local law enforcement – was where most of the action was happening. The Biden administration has actually really reduced the amount of interior enforcement that's happening.

Those requesting asylum, typically, just come to the US-Mexico border. The US-Mexico border receives refugees from all over the world. Anytime there's any kind of geopolitical activity, anywhere in the world, you will see people from the countries with unrest show up at the US-Mexico border to request asylum.

The world shows up at that border.

In normal times, when Title 42 is not in place, these people approach the border, cross into the country, illegally, and then request asylum. They are then screened and go to a detention center for what right now is an average of about three weeks. After those three weeks, they are released on a monitoring program until they are able to go through the rest of the process. The rest of the process involves going to an immigration court, and having several hearings with an immigration judge until that judge makes a decision.

The asylum situation is confusing because, I think, many people do not understand that you just can't ask for asylum from your bedroom in Venezuela. You need to physically get to the United States. Coupled with the concept of legal or illegal – and how you're doing this, can be tricky. Can you talk about claiming asylum – which is international law, and recognized by the United States.

There are a lot of misconceptions about this. After World War II, many nations in Europe, and then later the United States, got together to decide how to manage large populations of displaced people. And they came up with The Refugee Convention. The Refugee Convention, which the vast majority of countries in the world have signed at this point, is actually pretty basic.

It works like this: if you are fleeing a country as a refugee, ideally, you should be able to go to a safe place, register as a refugee, and then wait for the international community to find a place to resettle you. Unfortunately, because countries have not responded as much as they should have to the needs of refugees, many refugees in the world actually stay in these very dangerous, impoverished camps. Most are in east Africa and South Asia. Because other countries haven't accepted them, they just sort of languished there, not just for months, but literally years and decades. There are children who are adults now who have spent their entire lives in the camp.

Because the international system has failed to respond to refugee needs, many people, when fleeing situations of violence, decide they don't want to spend the next two decades in a refugee camp, and instead decide to go through the asylum process. To declare asylum, they go to a nearby country and request asylum upon arrival. Crossing a border for the purposes of requesting asylum is not an illegal crossing. It is not supposed to count against someone who is requesting asylum.

There's one final point that is almost never talked about in the news. Unfortunately, there are basically no refugee camps in the Western hemisphere, so there isn't even an option for people from El Salvador, let's say, to go to a UNHCR refugee camp. There are no refugee camps. And this is not an accident. Ever since the Monroe Doctrine in the 1800s, the United States has intentionally and consistently sought to maintain Latin America as its geopolitical backyard.

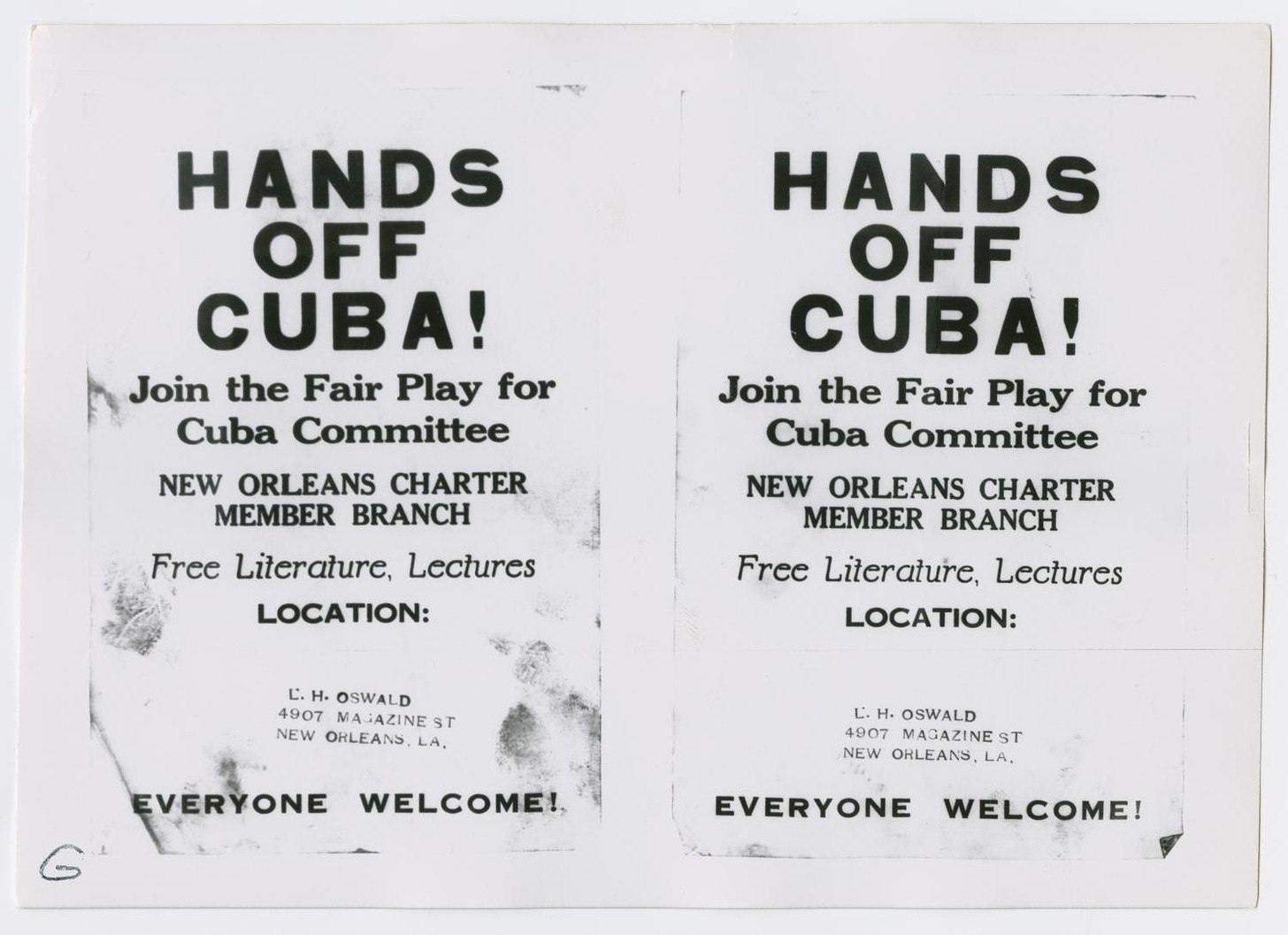

They have sought to limit interference from communist countries and Russia, but also Western European countries, who may otherwise have wanted to be involved in Latin America. The reason that you can't leave Venezuela and go to a refugee camp in Central America is that we have played a role in ensuring that that is not an option for those people. In a sense, US foreign policy has helped to create a situation where people's only choice is to come to the border and request asylum that way.

How does the U.S. benefit from that? What is the motivating ideology behind not wanting camps and forcing people to come to our border?

Historically, much of the political instability in Latin America has been a result of US foreign policy. Take El Salvador, for instance, where during the Cold War the United States supported the opposition to a democratically elected leader, who happened to be a leftist. The United States has contributed to the very violence in El Salvador that people are fleeing.

You can imagine how the scenario where the United States is supporting an oppressive regime in Latin America, and then all of a sudden allowing refugee agencies to set up camps outside of the country where the United States is helping to perpetuate the violence might look problematic. The United States is keenly aware of those optics, and it has, essentially, covered for itself by delegitimizing these refugees.

Who determines what is a valid or invalid claim of asylum?

There's one precise answer to this and there's one more philosophical answer. The precise answer is asylum officers at USCIS typically adjudicate those initial asylum applications. Since the nineties, a lot of the people arriving are put straight into the deportation process in the courts. So, today, most of those people are having their cases decided by an immigration judge in a courtroom setting. This is a bit problematic because these are refugees. The process of applying for asylum and going into court with opposing counsel is what we call an adversarial legal situation. That's not supposed to be how refugee applications go. They should just be going to an office, basically.

The Biden Administration has actually proposed a rule change to take those cases out of the immigration court and put them in the hands of asylum officers instead, in a non-confrontational setting. There are some issues with this — they claim to want to speed these cases, which could be an issue – but on principle, that is supposed to be asylum works.

Those are the basics of who is making the decision, but these individual asylum officers and judges don't live in the world of isolation. They live in a world where deciding on asylum cases is part of an entire ecosystem of knowledge – an ecosystem that is highly contrived and highly shaped by how the government documents information and which kinds of facts and experiences are legitimized.

When asylum officers and judges make decisions, they're also influenced by all kinds of other external factors that are shaped by US policy. For instance, the United States updates its Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. This is probably the most important documentation that goes into asylum cases. It documents all the human rights abuses that are happening in different countries around the world. Obviously, it can lend legitimacy to someone who's saying, for example, I'm a trans person living in El Salvador or Guatemala, facing persecution. If you go to the Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and see that, yes, the US government has validated that in Guatemala, there is severe targeting of trans people, and that lends legitimacy to that person's claim. However, those documents are very political documents. They're not merely factual.

Another thing is that political instability looks very different in different parts of the world. Political instability in Latin America, certainly, looks different than in other countries. It doesn't just look like one country invading another as we see in Ukraine. The nature of political instability and violence in Latin America, at least today, is a bit more of a complex system of corruption and violence between gangs, various police agencies, and governments. It's easier in that scenario for the United States to dismiss it. So all of these things kind of shape who gets counted as an “authentic refugee”.

Ukraine has shown a sympathetic side. You write about the role race plays in this.

There is a lot to say about having a clear and simple narrative. We don't seem to handle complexity very well, and U.S. presidents certainly don't have a history of handling complexity very well. A simpler narrative is obviously easier to sell, especially if it's a sympathetic political narrative.

But then the question of how to grapple with race is really important. It's not as if U.S. immigration law has really explicit racial exclusions. We used to, but most of that was stripped away in the 1960s. However, structural racism still shapes the US immigration system. One of the things I try to grapple with is the relationship between race and nationality. We have the racial binary in the United States and, much has been written on this, all other kinds of racial identities get constructed along the lines of white and black. This is true within US immigration policy, even when we're looking at countries where racial identities do not automatically map onto what it means to be black or African American.

For example, Haiti is a predominantly black-African country, it's not exclusively black, but that nonetheless affects people's perceptions. The way that the story about Haiti gets told very often falls into the same kind of racial narratives that are produced in the United States. Haitian migrants are going to be racialized as black when they're coming to the United States, which I think makes it demonstrably easier for the United States to characterize these refugees as criminals, illegitimate refugees, and people who deserve to be sent back to Haiti.

In Haiti, 500,000 children have lost access to education due to gang violence, @UNICEF says. Almost 1,700 schools are currently closed in #PAP; 772 schools in Croix-des-Bouquets, 446 in Tabarre; 274 in Cité Soleil, & 200 others in Martissant, Fontamara, Centre-Ville & Bas-Delmas.I mean, Haiti just had their president assassinated. There is this idea that this is a complicated, political story, but it's not complicated. There is severe political instability in Haiti – it just gets delegitimized. If you're in a black, predominantly African Cuban country, there's this historical narrative that political instability is just part of your culture, that these things are normal in these countries. This just happens. It gets normalized, and when something gets normalized, the people who are fleeing it are viewed with contempt. Like, “you should stay and fix your problem.” We don't see people telling Ukrainians, "don't come to the United States, you should stay in your country and fix your country."

Cubans too. There's lots of great research on this because, not all Cubans, but many Cubans are also lighter-skinned and fit more easily on the whiter side of that racial binary.

Sure, and there’s a narrative of a love of capitalism that helps too…

Exactly, very helpful. But as does being able to pass as white. Cubans have been able to be welcomed and integrated in a way that other countries, even in Latin America, again, many of whom are as capitalist-loving as Cubans have not been.

Panic is weaponized and politicized easily. Have you found a successful way of talking about the border without suggesting it’s in crisis?

There's this idea about these like ideological bundles – like people think that there is this, conservative, nationalistic, white supremacist whole bundle of political views that have to fit together. What I try to do as a teacher and as a speaker is to try to build a permission structure for people to understand that you can actually have different nuanced views that don't all go together.

You can be like a staunch capitalist and be an open borders capitalist. In fact, those ideas actually go together in a much more common-sense way than being a capitalist who is into closed borders does. You can also be someone who loves America and thinks America is awesome, and do not believe that we need to be militarizing the border. I think unfortunately what's happened is that these constructed ideological bundles go on to shape political campaigns. I mean, J.D, Vance in Ohio, where I'm from, is running on a platform to shut the borders down. Like, what are you people talking about? This is not an issue. It's just absurd.

DeSantis is asking a federal court to force Biden to turn away Cuban, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan refugees.Today, I established November 7th as Victims of Communism Day to honor those who have suffered under communism and remind people of the destruction communism has caused worldwide, including a death toll exceeding 100 million. In Florida, we will tell the truth about communism. https://t.co/Ojlao8f46tRon DeSantis @GovRonDeSantis

The militarization of the border is interesting in practice. El Paso, for example, is not only hyper-militarized at the border, but it is also home to Fort Bliss. And, the median income in El Paso is less than $24k a year. The role these industries play in the local economy really complicates the politics.

I think this is the stickiest part of the immigration system. This system works like the military works, frankly. These systems work because we have considerable economic inequality and a lack of easy access to higher education. If you want to go to college and you don't have money, the two main options for you are to join the military or become a cop. I mean, this was me. These clear paths to a stable income and job, as well as social recognition.

There's a kind of cultural capital that accrues in these roles, and that builds into its own perpetual machinery. There is a massive apparatus of jobs that are tied to the militarization of the border, so if you try to scale things back, you really are taking away people's jobs. I saw this when I was working at the family detention center in Texas. They were busing in hundreds and thousands of workers a year from places in the south where there was a lot of poverty – and that's no accident. These people’s livelihoods are then intricately tied to the detention and deportation of other people of color from south of a border. It just builds a very troubling system. Once people's jobs depend on this system and there is an economy built around it, it's really hard to change.

But, to get back to your question about migrant flows and crisis language – I mean, I think you're right. There's a weird kind of nationalism baked into believing that everybody wants to come here. People don't want to live in poverty, they don't want to live in a civil war, but they don't necessarily want to come to the United States.

The United States has played a massive role in producing economic and political instability that is forcing people to come here. It is this vicious cycle of “America First” policies – where national interests are producing the circumstances in the world that are bringing people here. International intervention is not going to produce secure borders, it is only going to drive more migration.

Right.

And even if it didn't – migration is a human phenomenon that has been going on for years. Borders are maybe 150 years old. Sure, the Roman empire had some walls, but they were not a migration control system. They didn't prevent people from moving; they were a political marker, not a real boundary. 200 years ago, you couldn't live in a world where you would go through a border checkpoint with a physical border barrier that was trying to prevent you from crossing. Even the Great Wall of China was never about preventing actual movement. This is all to say, the most historical examples of walls are not borders in any sense of the way that we think of them today.