Our Future Makers

Paris Marx on different visions for the future, the Silicon Valley mindset, and walkable cities.

If you haven’t heard London is burning, a wedding in Hawaii got swept away, and everyone (on Twitter at least) is mad they don’t live in a walkable city.

None of this just happened. As we look to what we want our future to look like, it’s important that we heed lessons from the past and ask who is selling us this vision and why?

Paris Marx, author of the new book Road to Nowhere, spoke with us about different visions for the future, the Silicon Valley mindset, and walkable cities.

This interview was conducted and condensed by Noelle Forougi for franknews.

So nice to speak with you today – it would be great if we could start by you telling me a little bit about yourself and how you got into this work.

Yeah – I get this question a lot and I'm like, how did I get into this work?

I guess the short story is I started to write about cities, transportation, and its relationship to technology back in 2015. Over time, my writing expanded to looking more broadly at the tech industry and its history and the products the tech industry was putting out there.

Then, I went back to school in 2018 and did a master’s in urban geography, specifically looking at Silicon Valley's ideas for the future of transportation. Once that was done, I thought that the work I had been developing over a number of years would probably be a good topic for a book. I took some of the writing and research I had been doing and reframed that for a more general audience rather than an academic audience.

I think the focus on the Silicon Valley mindset, the world, and the people is fascinating. How do you define the Silicon Valley mindset? And, how do you describe the Silicon Valley mindset as it pertains to mobility?

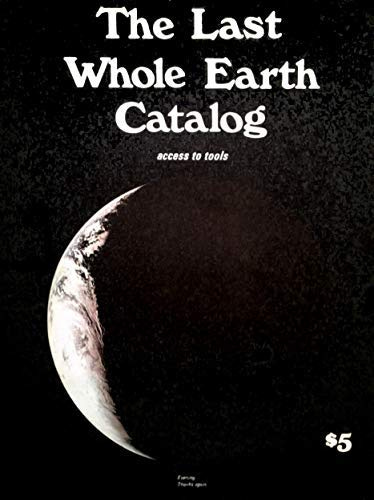

I'm obviously pulling from a lot of other people who've done work on this before, like Fred Turner's great book From Counterculture to CyberCulture and Richard Barbrook’s book The Californian Ideology, to inform the way I understand how Silicon Valley approaches these things. I think it's important to go back to the 1960s and 1970s and look at the libertarian ideas that are coming out of that moment. There is the Whole Earth Catalog, which Stewart Brand is promoting, which Steve Jobs then picks up to promote the personal computer.

During the counterculture, there are two dominant strands of thought that Fred Turner identifies. On the one hand, you have the kind of new left that wants to see political change and wants to engage politically. And there is another strand that is more focused on the idea that changing society starts with changing the individual. It's about having these psychedelic experiences to change how one feels personally, and that is how one changes the world. And that is connected to this idea that personal technologies are gonna be one of the ways that you empower the individual to make these changes. We see those ideas in the marketing of Apple and the personal computer; Steve Jobs is repeating these sentiments.

These libertarian ideas that come out of that moment, end up fusing together with the neoliberal, capitalist ideas that emerged in the 1980s with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. You end up with these libertarian ideas about the power of technology and the empowerment of the individual, linked with the idea that we need a free market to promote entrepreneurialism. And, the role that the government played in making Silicon Valley what it is due to all the money that was being funneled into the Bay Area during WWII and the Cold War, is downplayed in favor of a more market-oriented narrative around technology.

There's one other essential piece to all of this I'd mentioned, pulling from the work of Jarett Walker, which is this idea of “elite projection.” This is the idea that the innovation from these tech companies, particularly in the past decade or so, comes from a set of people who have a particular experience of the world and a particular idea of how the world would work. Their experience informs how the world should work and how technology should change things. I mean, Uber comes out of the idea that Travis and his buddies couldn't get a taxi cab.

Right, the focus on the car itself, with Uber and Tesla, feels like such a manifestation of this libertarian, individualistic mindset. I'm curious how all of these elements you just laid out go on to inform what tech’s vision of the future of mobility is.

Well, I think it's so interesting as well because even when the personal computer is emerging, one of the things Apple says as it is promoting it is the Apple computer is like the Volkswagen, it's empowering the individual in the same way. They are making these connections to the kind of individualist narratives that were associated with the automobile and now applying them to the personal computer.

You mentioned Tesla, and I think Elon Musk is a good example of elite projection; you have someone in this elite position who has this particular idea of, in this case, how the transportation system should work. Elon Musk has this kind of opposition to public transit in a really fundamental way. There is an interview where he says that transit is unsafe, there could be a serial killer, it's inconvenient, and that he doesn’t understand why anyone would want to take this form of transportation.

The answer becomes individualized transportation. Someone like him wants to stay in a car, away from people, and not in traffic. From there, you get all these kinds of wacky ideas for how to get around all these problems of the transportation system – a bunch of tunnels under the city to fix traffic, even though any transport planner can tell you that would never actually fix traffic or the promise of autonomous vehicles. We have been promised self-driving cars are just around the corner for decades, and, I mean, where are the self-driving cars now? Sure, there are few around some cities in the world or in the United States, but it hasn't really fixed these problems.

I think we need to realize the kinds of ideas that these people are putting out there are serving their own ideas of what the future should be and how society should work. We need to question whether those ideas are ones that benefit the broader public, or just a certain type of person at the expense of everybody else.

I'm curious about the role of policymakers in all of this. They don’t necessarily seem to be putting forth a coherent vision, but rather letting Silicon Valley take the reins and then regulating reactively. Are they somehow stymied by the private industry? How do you see them interacting?

I think it's a big problem. I think the ideas that emerged in the 1980s around leaving more and more to the market and industry play an important role, but I don't think that that always serves us best. I think that part of the reason that Elon Musk has been able to achieve this position in society and to be seen as a kind of a “future maker” is because there has been such a dearth of imagination or big thinking within the public sector and among our elected officials.

The outcome of that is that these tech companies can propose virtually anything they want and can implement them in our cities. It's only later that policymakers try to come in and kind of rectify the negative aspects that have come and ask whether this is something that we should have adopted or allowed to have taken place in our city. Is this actually benefiting the public?

A perfect example of that is the Boring Company projects that are being sold around the United States. The project in Las Vegas is basically a glorified Disneyland ride, in my opinion. There's one in Fort Lauderdale, where the town kind of went to the Boring Company, and said, “we need a tunnel for this train because our bridge is really old.” When they signed the agreement with the Boring Company, there was no tunnel for a train, but rather a tunnel for Teslas to go to the beach instead.

The government plays a really important role in setting the foundations for the kind of transportation structures, and for the broader society that we have. One of the reasons that I wanted to go back and look at the history of automobility and the emergence of the automobile in the book was that it really illustrates the important role that the state played in remaking our transportation system and our communities to facilitate the mass use of the automobile.

There were a bunch of commercial interests, the automakers, the oil companies, the suppliers, that aligned behind this vision, but that wouldn't have been able to happen if the government hadn't heavily subsidized it, hadn't changed regulations, and hadn't encouraged the construction of all these roads and highways oriented around the automobile. If we think about how we're going to solve these problems today, it's not just by unleashing some new technologies into cars or whatnot. The government really does have a key role to play in ensuring that these more foundational changes happen.

It feels like a difference in what kind of future is being sold. There is one that is flashy and sexy and about exploring space and having a big personality, and the other, maybe a bit boring in comparison, about making things a little bit better for everyone. How do you compete against a more exciting vision of the future?

Yeah, it feels a bit less sexy to say let's just invest in the bus instead. One thing that I think about a lot when it comes to the future visions being put forward by a lot of these powerful, wealthy folks in the tech industries is who are these visions actually serving? And where do they come from? A lot of these founders and tech billionaires are inspired by science fiction that they've read, and in many cases, it's dystopian science fiction, but they fail to take lessons from it. And they look good because they're like the builders they're bringing to the future without questioning whether this is the future that we should be trying to achieve.

We were promised that social media was going to have all of these good impacts, that Uber was going to make the transportation system better, and that self-driving cars were gonna be around in a few years and make everything amazing. And a few years down the line from these projects, we have learned time and time again that these promises are not going to be fulfilled. Again, we need to ask who are these visions serving?

I think we actually underplay how popular and attractive the idea of investing in improving public transit, making cycling infrastructure better, and investing in public housing is because of how these ideas from people like Elon Musk tend to dominate the media conversation.

Can you speak more about where we should be focusing our energy instead? Are there specific projects that you would point to? And does this have to come from the state or federal level or do local governments have a role to play?

I think that there's a place for every level of government to be thinking about these things. I think that municipalities and cities can start making some of these changes, to make people think about what's possible. Even during the pandemic, we had some moments of that when some cities would close streets and restaurant dining moved outside. People realized what life could look like if they started to take back some of these areas of public space, and that we can think of different ways of organizing our communities.

I would say that I think an important piece of this does have to come from the federal or at least the state level because they set so many of the regulations and decide how much of the funding gets distributed in particular ways.

That doesn't mean that there aren't things that lower levels of government can do in the meantime. In Los Angeles, for example, in recent years they've passed ballot measures to put a lot of funding into the public transit system there. I think investing in public transit is really important because it allows people to get out of their cars and offers them proper alternatives. Ensuring that the cycling infrastructure is there makes people feel like they can be safe and like they don't need to worry about being hit by a car is important.

But, one of the things that I say in the book is that it can't just be about the transportation system. The transportation system is one key piece of this, but we also need to be thinking about like the wider systems. If you improve the transit system in one neighborhood, that causes the price of housing in those communities to go up. We have to think about the degree to which we have allowed private companies to take over so many aspects of our lives. Should housing be an investment that just allows private companies and increasingly private equity companies to just keep jacking up the rents as much as they can on us? Or should we think about how to restructure these things in a way that is best for all of us?

It's depressing to think walkable communities are, like, a luxury good.

Yeah, it is terrible to think about that, but we've seen it in Los Angeles – people were opposed to new cycling infrastructure or transit improvements because they know that property prices will rise and that they might be pushed out. Some might consider that NIMBYism, but, really, I think it's a very understandable approach to say, “I don't wanna be priced out of my community, even if that means I'm gonna miss out on cycling infrastructure or a faster bus line because this is the neighborhood that I'm used to.” Protections need to be in place for people so that they can afford to both live in their communities and get these other benefits.

I know you talked a lot in the book about the history of how the US became dominated by cars. You focus also on the activist movements that organized against this. There were some wins, but not at a mass scale. Are there any lessons to take from these activist groups?

There are so many examples and that is one of the reasons that I look back at the history in the book. In the 1920s when the automobile was emerging, groups formed in the American cities, as Peter Norton describes, to push back against the entry of the automobile and the way that it was disrupting the norms of the street at that time. They take loads of actions to draw attention to the fact that these automobiles don't fit with the norms and are killing people on the streets. Ultimately, unfortunately, they fail and the automobile does take hold, and our communities are remade.

But at the same time, we can see in the 1970s, which is a moment somewhat like today when gas prices and energy prices are going through the roof, in Europe, where the entrenchment of the automobile comes a bit later than in the United States, there are groups there that push back against this. Obviously some of the most successful are in Amsterdam and Copenhagen, and the Netherlands and Denmark more broadly. They organize to say we should be more focused on cycling and these other modes of transportation. And that's not to say there are no cars in Copenhagen, but they were able to effectively push back on it.

There are many examples throughout history where we can see how things can be changed, but we also need to recognize, especially when we're thinking of the North American city, that automotive interests are incredibly powerful. That's why the conversation right now is focused on replacing vehicles with internal combustion engines with electric vehicles, rather than whether we should be focused on getting people out of cars altogether. This presents the greatest profit opportunity for the companies who are involved in the development of these vehicles. When you challenge that, you're also challenging a whole kind of economy and group of economic interests that enjoy the status quo, that profit from the status quo, and that would rather it not change.

It's always going to be a big fight, but I think that it's an essential fight in order to address the problem of climate change, make our communities more livable, and improve our quality of life. Hopefully, we can be not so indebted to capitalism and the need to turn a profit, at the expense of us and our wellbeing.

![[Dallas Love Field Airport : Construction]

[Sequence #]: 1 of 2

[Dallas Love Field Airport : Construction]

[Sequence #]: 1 of 2](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdcbac430-95b0-4e0d-bd1c-7b282947cb76_1500x1031.jpeg)

![Men by Computers

[Sequence #]: 1 of 1

Men by Computers

[Sequence #]: 1 of 1](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdc3b269b-7298-4b7b-91c1-d10cb97c7e6d_1500x1195.jpeg)