Spatial Justice, Surveillance, and Shade

In conversation with Ersela Kripa on El Paso and the purpose of architecture.

![large representation of [Aerial View of the Rio Grande River]. Side 1 of 2 large representation of [Aerial View of the Rio Grande River]. Side 1 of 2](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3a5ab0f7-823c-45fb-9532-b894ac812696_1500x1219.jpeg)

There is a difference between an innate or intellectual understanding of things. Being physically present with infrastructure as large and dynamic as an international border isn’t always a given when discussing the politics that surround and then swallow an international border. Today’s interview covers both the unmissable anecdotal needs of those who cross the border every day (namely shade), and the need for a more modern pedagogy.

I do feel that architecture and designers need to really take a position. I don't understand how the profession or the discipline is still wondering if it is political or not. I feel like the argument that it is has been proven a long time ago. I think we need to broaden the discipline where the practice is really taking in the full context of its impact on the basic political rights of humans and non-human creatures. So many of our decisions are just based on our moral compass, right? We can do so much damage.

This interview with Ersela Kripa, an architect and founding partner of AGENCY, was conducted and condensed by Tatti Ribeiro for franknews.

Would you introduce yourself and tell me a little bit about where you work and what you're working on?

I'm from Albania originally and, through a really long story, I ended up in El Paso. I've been in El Paso for seven and a half years. I co-direct AGENCY, which is a private architectural practice where we work on specific issues of spatial justice in urban environments as they are, essentially, co-opted by a military thinking of cities. I also direct the College of Architecture at Texas Tech in El Paso and co-direct the research center here called POST (Project for Operative Spatial Technologies). We look at issues of urbanization and desertification as they impact urban human migration – so that involves looking at environmental justice, ecological justice, and social justice.

How would you describe spatial justice?

It's a tough question. As an architect, I know it, but verbalizing it is something else. We look at the unjust distribution of resources in public and private space, as well as the loss of rights in public space. So we assume we have specific rights as they are guaranteed by law in public space, but those rights become really unevenly distributed depending on who the person is, what their background, and what their goals are, and also due to the increase of militarization, of cities, of surveillance, of the blurring between police and military technology and aerial surveillance. We saw this in the Black Lives Matter movement in the spring of 2015 where there were unconfirmed FBI helicopters overhead collaborating with Baltimore police to aerially surveil protestors who were just exercising their right in public space. So it's about how we imagine we have rights and how those rights are inequitably rendered.

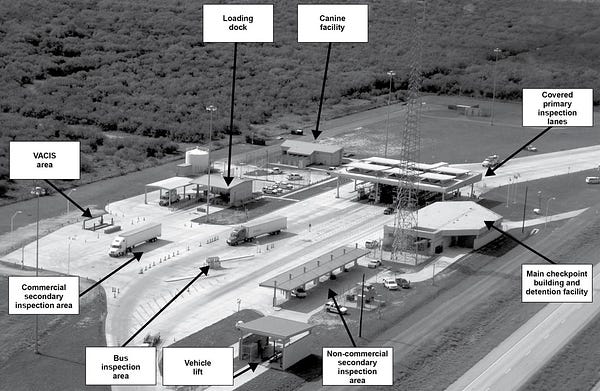

El Paso is specific in that there’s a more permanent structure of surveillance, because of its proximity to an international border. I read a quote from you that basically says how we look at architecture and how it's used by governments constructs an aesthetic that becomes a way of life. Can you talk about this in terms of El Paso? What has the militarization of the border done to that space?

At a very basic ecological level, the channelization of Rio Grande and the binational treaty to create these dams and these control mechanisms have not only solidified the US-Mexico boundary in really ossified ways, but it also had a negative impact on human and non-human species on the border. The idea that a river, a natural body, needs to be controlled and that water needs to be measured is absolutely absurd. And what I notice is that we are in the Chihuahua Desert, and we are continuing to desertify, and that unevenly impacts people who live in the borderlands depending on income level. The impacts of climate change are unevenly felt across the Mexico border, especially in El Paso and Jaurez. Neighborhoods that are more pedestrian, where people are waiting at bus stops longer, are completely lacking shade and protection from the relentless impact of the desert.

I never spent time in El Paso before the militarization of the border, so I really don't know another vibe. When you speak to people who have been there their whole lives, they talk about the change not only in their personal experience crossing, but also the change in the landscape. The view from many homes is a wall now. I had never really thought about an aesthetic being imposed onto a city in this way. Your work with POST is action oriented. I'd love to hear a little bit more about what you are working on.

When we first moved here and we were trying to establish this research center, we realized that even data and information is so fragmented across the boundary. The way both countries measure specific environmental and demographic data is just so different, in terms of scale, in terms of priorities, and even in terms of units of measurement. We decided to establish the border consortium where we are reconstructing data in a way that stitches the data boundary between the two nations.

And then, we've been able to ask the question, what does this mean for design? What does this mean for action? How can we imagine better environments? And so we've developed a workflow that moves us from satellite data into GIS, which is a digital mapping software platform, into Rhino and Grasshopper, which is architectural software, as a way to look at issues of inequity in shade in relation to demographic data of who is actually spending long periods of time exposed to sunlight.

So it is usually migrants or daily workers who are crossing the border. And we're able to calculate a very specific way in which we can design the geometry of shade structures that protect against UV damage in really precise ways. One thing we found out is that because we're in the desert, the air is filled with particulate matter and that particulate matter reflects more UV rays, so we are less protected in the shade here than you would be in a city that doesn't have that much dust in the air. So how do we protect this kind of environment? We've been able to essentially take this enormous amount of deep data and turn it into an actionable geometry and fabricate shade structures that could be deployed and protect people when they're waiting at crossings or bus stops.

That is so obvious when you say it but I think very far from the average thought about what the border needs. Who are you hoping looks at this research? Who are you trying to talk to and who has interacted already with the work?

In a straightforward way, this translates into research, pedagogy, and teaching. At a policy level, we're talking with the city of El Paso's Resilience Office. The Resilience Office is doing amazing work on climate change and economic resiliency. We're working with their office to make this UV analysis tool available in urban environments. And we have talked to the county commissioner who is looking at issues of access to public space in the city. So asking, how does public space get distributed that is actually viable in a desert context? And through the Border Dispatches through the Architects Newspaper, we were publishing these monthly issues on specific kinds of injustices or specific types of militarized mechanisms of control that directly relate to space. So detention centers, the private border wall built by Steve Bannon.

Cool. Where will the shade structure be?

We're working with Insights, a nonprofit science organization that teaches kids about science. El Paso was under the Permian Sea millions of years ago. So there are fossils and there are dinosaur footprints at a very specific site where Insights offers outdoor science activities, but, as you can imagine, in the summer, they can't really teach kids classes outdoors unless it's like 5:30 AM. So we are partnering with them to build an outdoor shade structure for their events.

I'm curious, in spaces that have been heavily militarized or are dealing with detention, have you seen successful examples of de-escalation? Like once it's built, is it over? Or can it be undone?

The answer is no. Unfortunately, a very specific example is this private wall that Steve Bannon built. That thing has enormous deep foundations filled 60 feet deep with soil before the concrete was poured. And so that is a future archeological object. It's not going anywhere. There doesn't seem to be a de-escalation.

We wrote a book called Fronts, which looks at the history of military urban warfare training and doctrine development since before World War I, and the trend seems to be that the military is essentially training more and more and building more and more of these urban environments for warfare training, which therefore translates to reading urban contexts as zones for military penetration. I mean, budget appropriations always favor military and DOD contracts. It seems like it's here to stay both ideologically but also financially it's such an embedded part of American economics.

Do you feel a particular urgency about anything right now in your work? In El Paso or elsewhere?

I do feel that architecture and designers need to really take a position. I don't understand how the profession or the discipline is still wondering if it is political or not. I feel like the argument that it is has been proven a long time ago. I think we need to broaden the discipline where the practice is really taking in the full context of its impact on the basic political rights of humans and non-human creatures. So many of our decisions are just based on our moral compass, right? We can do so much damage.

I think that's really urgent because then it translates to the way in which we educate. It translates into graduating students' understanding of architecture and its impact on the built environment and its impact on people's rights. It's a long convoluted answer, but I think we need to really urgently shift attention to very specific issues of what it means to be a political citizen and a political kind of architect.