The Guardians of American Culture

An Interview with John Fea on faith, nationalism, and Seven Mountain Dominionism.

If you’re wondering what Seven Mountain Dominionism is – same. We wanted to speak to John Fea about his research and analysis about the particularly American elements of Christianity and evangelicalism. How religion bleeds into politics. How politics becomes like religion. We got so much more in this conversation. ‘Twas eye-opening!

This interview was conducted and condensed by Tatti Ribeiro for franknews.

My name is John Fea. I've taught American history at Messiah University for 21 years. I have written six books, mostly on early American history and American religion.

Were you always curious about religion or theology in this way?

Relatively speaking, I've had a diverse Christian life. I'm half Italian and half Slovakian, the grandson of immigrants, raised in a Catholic family in Northern New Jersey – so Catholicism kind of came with the territory. When I was 15 or 16 years old, everyone in my family had an evangelical conversion experience, so I spent a significant part of my life in the evangelical Christian subculture. I still identify as an evangelical today. I'm not sure how much longer that word is going to be useful to describe my Christian faith, but I've always been interested in religion and American history to understand my family's experience in America. I have a Ph.D. in history, but I got interested in religion simply to try to sort out and make sense of this kind of interesting faith background.

This is not meant to be a personal conversation – but I am curious about this conversion experience you mentioned.

My book, Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump, does have some autobiographical material in it, so I'm happy to talk about that. So, again, my family was culturally Catholic. I was confirmed within the Catholic church. It was really my father who went through a crisis of faith in the late 1970s. He was a general contractor and home builder. He really got hit hard financially by the high-interest rates during the Carter era, and we ended up losing our family business, which led him to go on a kind of existential search for meaning.

And my father had a lot of religious questions that our local priests did not seem to have good enough answers for. My Catholic friends today tell me if my father had a good parish priest, I'd still be Catholic. But actually, he ran into a group of evangelicals on a construction site, and before we knew it, he was attending bible studies in this evangelical church. And within a couple of years, all of the members of my family had left the Catholic church and embraced evangelicalism.

How do you view, in your own life, and in your research, the connection between America and evangelism?

Well, in some ways, historically, evangelical Christianity is a deeply American form of faith. It goes all the way back to the time of the American Revolution. I mean, if you asked people through the 19th century, and probably up until World War II, "are you living in a Christian nation?" most of them would answer “yes,” and they would probably also believe that they were living in an evangelical or Protestant nation. Protestantism especially has always been perceived as a religion of freedom, when compared to Catholicism. In Catholicism, a Protestant would say, you're not free to read the Bible the way you want, the priest tells you what to believe – these are all stereotypes, but this is the way Catholicism was understood. This also explains a lot of the sort of fear of Catholicism during the 1960 Kennedy election. Protestants wondered if they could vote for a Catholic president because of the Catholic’s loyalty to the Pope. Evangelicalism and American democratic ideals meshed very well in the 19th century.

Evangelicals were the guardians of American culture, and then in the 1950s, there was a Catholic, Evangelical, Jewish synthesis. In Protestant, Catholic, Jew the sociologist Will Herberg wrote about this. But by the 1960s, Christians started to feel threatened. There was the loss of prayer and the loss of Bible reading in public schools. The 1965 Immigration Act brought diverse groups into the country. There was Roe v Wade. All of this triggered a certain degree of fear in evangelicals about losing their culture, and so after 1980 evangelicals, especially politically conservative evangelicals, went on a crusade to win back the country.

The description of Evangelicals as preferring their faith to Catholicism citing “freedom” feels a little antithetical to the desire to control mass culture. If it is so personal, what is this obsession with culture?

Well, that's the paradox that historians have wrestled with for years. How does a group that comes over in the 17th century to Puritan New England, pursuing religious freedom, suddenly set out to create a society which has very little religious freedom? This paradox has been there from the beginning. I think many evangelicals would put it this way: we believe in religious freedom, but true freedom is the freedom to worship God in the right way. That will bring you true freedom, whether it be in heaven or in a more moral society.

Do you think we are still living in a Christian nation?

It depends on what you mean by the phrase “Christian nation.” In terms of demographics, America has always been overwhelmingly Christian, but if you look at it in terms of the founding, it's very difficult to make an argument that the founders wanted to create some kind of Christian nation. I think they wanted to create a nation where religion was not condemned or marginalized, but where religious liberty flourished.

I think there are a lot of evangelicals today who have wed their understanding of the kingdom of God with their understanding of America – as if the United States is some kind of exceptional nation because God has uniquely blessed it. You hear this phrase “city upon a hill,” where the US is painted as a beacon of freedom and liberty and religion and Christian faith to the world.

I think that it is a really, really, really, really bad thing to fuse faith and nationalism. As an evangelical, I see this as not only undermining the founding ideals of the separation of church and state, but I also tend to see danger in this for the sake of the church. It is losing its witness, it is losing its prophetic voice in the culture.

Why do you think it’s still relevant for politicians to declare themselves as religious, as Christian’s specifically?

It's politically expedient to do so. I'm not sure I want to go that far to say that presidents don’t believe what they are saying – I am sure many of them do – but this goes back to the history of our country and what we often describe as civil religion. This is "One nation under God '' in the Pledge of Allegiance or Abraham Lincoln at the Gettysburg Address using conversion language. These kinds of biblical allusions and Christian references are everywhere in American culture.

So, as much as the First Amendment says there can be no establishment of religion, the way that this country developed, which is overwhelmingly Christian, suggests that these Christian symbols, these Christian phrases, and these Christian references are always going to be present. As one historian put it, there's a wall of separation, but that wall has many checkpoints where religion moves into public life. We have chaplains, we have Christian chaplains in the Senate and the military, right? We don't have a clear separation of church and state in this country. There are all kinds of examples where faith seeps in and those symbols tend to be Christian, and that becomes useful for politicians to use in campaigns to make people feel comfortable with their place in the United States.

It feels less common for people to be religious but the power of religion in politics is growing.

Yeah. I mean, that's true. A very recent study that just came out suggested that in the United States, the number of self-identified Christians is declining, and it's been in a decline for the last decade or so. One might say that the rush to people like Donald Trump or to the MAGA movement or the America First Movement is a kind of last-ditch effort to save a Christian culture.

I think what you often see in American history are populist movements like Christian nationalism, or candidates who position themselves as political saviors, appearing in periods of desperation when the people are trying to reclaim something that has been lost and that is probably never coming back. They are nostalgic for an age that never even existed in the first place, an age that they have constructed. It doesn't surprise me that we are seeing these populist movements appear at this moment.

What strikes me is that many of these Christian Evangelical leaders who are trying to promote this idea of America as a Christian nation seem to be tone-deaf to the fact that many people in their congregations, and in Christianity generally, may be leaving the churches for the very fact that their leaders are trying to exercise political power in this way. As a college professor who teaches Christian students, I know a lot of young people who are deeply turned off by the Christian Right. They're much more interested in things like social justice or the environment than previous generations. They're much more open to things like gay marriage, and they’re getting fed up with Baby Boomers who are trying to craft a Christian nationalist agenda.

If the idea is to move towards a theocratic nation, maybe the drop-off is okay. I was wondering if you could describe some of the philosophical underpinnings of the Republican effort. And particularly the role of people like David Barton?

This effort has been going on since the 80s. David Barton is a conservative Christian right activist who uses the past to promote his political agenda. Notice what I didn't call Barton in that description – a historian. He cherry-picks from the past to find something useful to advance his front in the culture war.

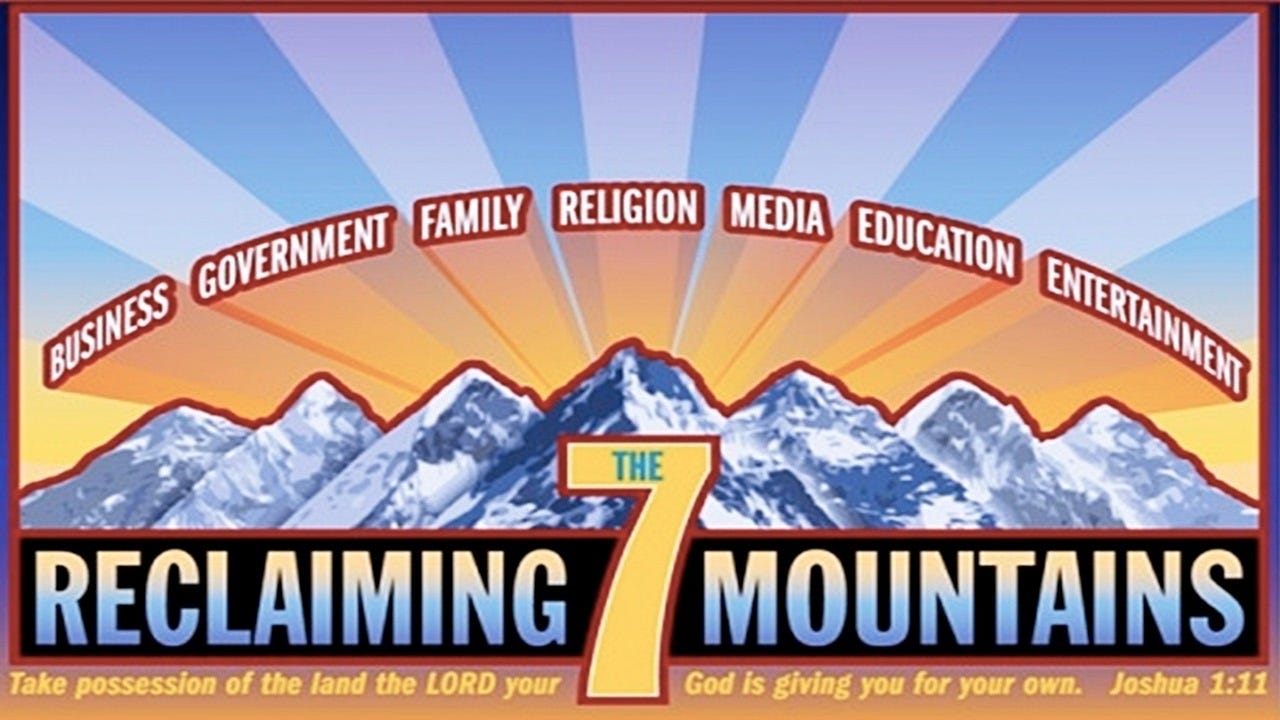

And he is very much connected to, if I’m not too deep in the weeds here, a theory called Seven Mountain Dominionism. This might strike some of your listeners as kind of crazy, but this is the theory that Doug Mastriano is running on right now for Governor of Pennsylvania. Ron DeSantis speaks at these conferences. Lauren Bobert and Marjorie Taylor Green are involved. The idea behind Seven Mountain Dominionism is that there are seven mountains of influence – education, religion, family, business, government, entertainment, media – that Christians need to reclaim or take over. And in some versions of this, once Christians have controlled these spheres of influence, it will usher in the second coming of Jesus Christ.

I see you are smirking, and I smirked too. I mean, for years, I just dismissed this stuff as fringe, but now you have candidates literally running on these platforms. The more this kind of Trumpism, or Christian Trumpism I would call it, takes over the Republican party, the more rational and traditional conservatives are going to get pushed out of the party. The Republican party has, in many ways, become the party of these borderline theocratic dominionists, who want to not only claim these spheres of influence, but want to show that America was once a Christian nation, it has lost its way, and we need to reclaim and renew and restore that Christian founding.

They've captured audiences through their massive speaking tours, and the really bad "history" books that they write. They're the most powerful figures in the United States right now that most Americans generally don't know about.

The preoccupation with politics in any church is wild – I interviewed a Catholic nun recently who housed undocumented migrants. I asked if she ever felt conflicted because of the law. She laughed in my face. She was like, I have God – I don’t need some senator telling me how to act or what to do when I see suffering.

Well, this testifies to the power of the religious right for the last 40 years in this country. In some ways, the Christian right has been the most populous, politically effective movement in American history over the last 40 years, maybe since World War II. They've taught millions and millions of evangelical Christians that there's only one way to engage the world politically. I think your nun is suggesting that there may be another way, right?

If you think about politics less in terms of elections and more in terms of a posture that pays attention to what is going on in the world and then asks,”what can I do to help?” you will arrive at a different vision of Christian politicians. It is a political act to bring a cup of soup to your sick neighbor. But the evangelical community has, because of the influence of the Christian right, embraced a view of politics that is totally related to power.

Evangelicals have no language by which to talk about politics and as a result they gravitate to one or two things: abortion, same-sex marriage, or "religious liberty." Their understanding of religious liberty focuses on the religious liberty not to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple. The Catholic Church, of course, is in no way unified, but at least it has a history of political reflection. The Church has developed a more robust understanding of how to engage the world politically than what the Christian Right has promoted.

I think this has a lot to do with the long history of anti-intellectualism within the evangelical movement. They don't have a kind of rich tradition of faith and reason to draw upon like the Catholic Church, which has ideas on these matters dating back to Augustine or Aquinas.