The Right Way

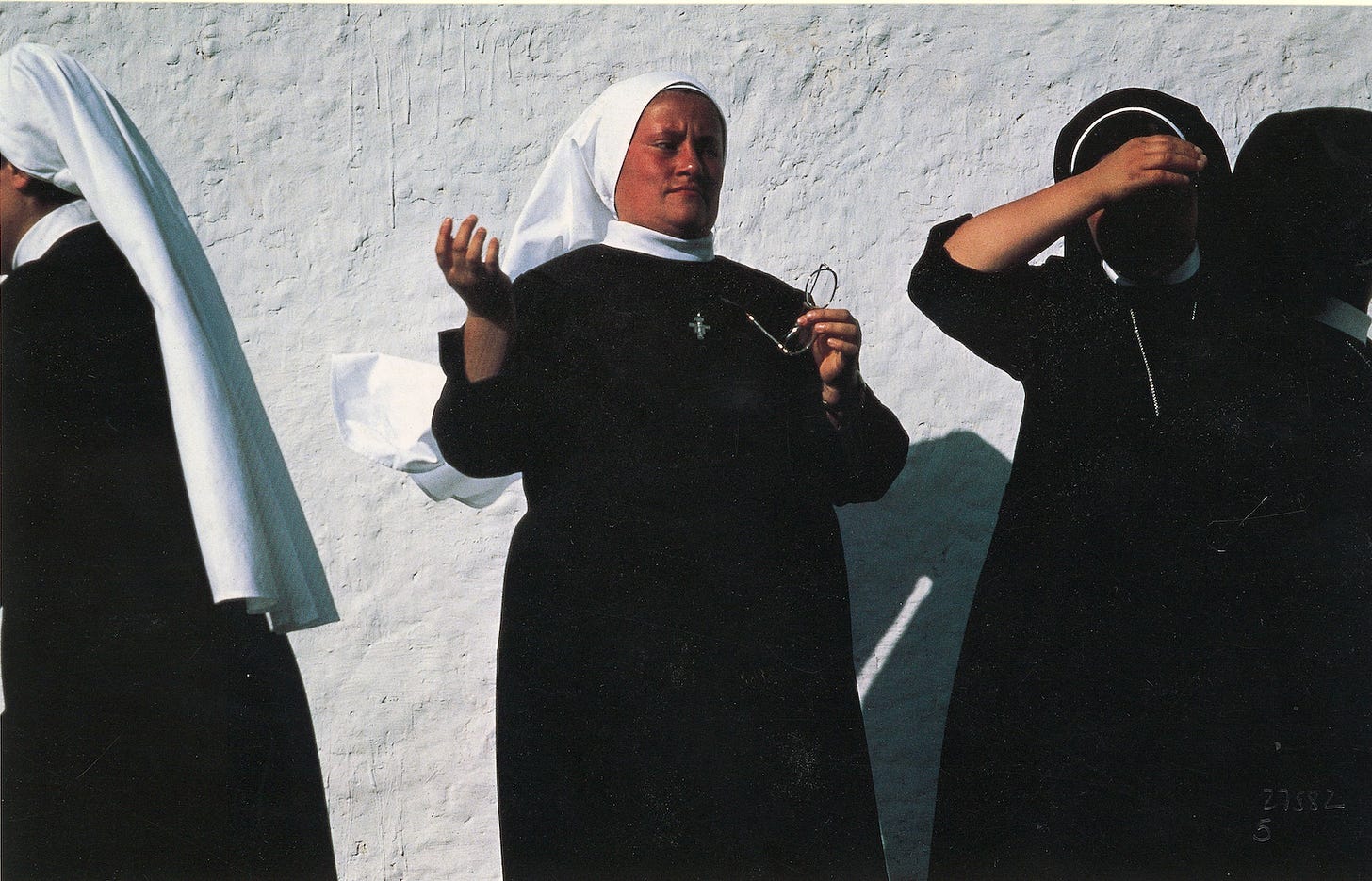

Father Garcia, a Jesuit priest at Sacred Heart Church El Paso, at the gate of migration.

Our third interview for the Border Issue features a conversation with Father Rafael Garcia of Sacred Heart Church.

This interview was conducted and condensed by Tatti Ribeiro and Noelle Forougi for franknews.

Well, I'm a Jesuit priest, and I was born in Cuba. I originally came to El Paso as part of a team to work on the border in 1994. Being here changed my life. Just seeing the reality of the border, which was pretty much unknown to me, even though I had worked in Tijuana, Mexico, before, was critical. I became acquainted with the systemic injustices and discrimination that have persisted for decades.

At that time, around 1994, the suffering was mainly with Mexican families being separated by deportations and stuff like that. It was more local. Then I left for nine years, went to two other cities, Albuquerque and Kansas City, and then came back here in 2016 to work with migrants and refugees. I was helping at shelters, going to the ICE Detention Center to do mass, things like that. And then in 2020, I became the pastor here again. The turning point was in December 2022 when we started the shelter here at Sacred Heart.

At that time, there was a large Venezuelan population gathering around the church. Our church is very centrally located. The bus stations are around here. People come to this area to look for and to find work. Sometimes people come from Juarez and get work. It's a very busy old neighborhood. And in 2022, we started to see a flow of families and children around here. There were times when they counted over a thousand people outside.

We would try to send them to shelters, but there came a point where the other shelters said, "We can't, we're full." So, we decided we had to open a shelter. Our building, which is an old school, has a gymnasium, so we opened one there. We started with nothing; we found some volunteers, and people to cook, and another parish helped us with volunteers and bringing some meals. Then little by little, we found someone who became the director. He had experience in shelters, so we organized a team.

When this all came out in the media, we began to get donations on the internet, which was amazing. We couldn't have continued without them. Some days we'd get $5,000 in donations in one day when the media was here. Things have gone down since, but we have gotten some grants that keep the place going, and since April, we have tapped into FEMA funds through the county to help with some of the expenses.

You said that working in El Paso really spoke to you. What was it about this place that drew you to it? What is different about working here versus working in Kansas City for example?

Well, first of all, we are right in the middle. We are at the gate and the gate becomes the news. Now you see New York and Chicago in the news, but you don't see migrants in Houston or other places. The entrance point is where a lot happens, and people get overwhelmed. We get overwhelmed.

But, this neighborhood, which is one of the poorest neighborhoods in the United States, has been very tolerant. People sleep at the front of their homes, in front of apartments, in front of their businesses. It's very different from other parts of the city. I know of another shelter, which was part of a church in a residential neighborhood, and it closed soon after opening because people were complaining. People here, it’s their roots almost. It has always been a binational place. Maybe they have family in Juarez, they get it. But like anything, it's never totally black and white. There are also a lot of people who are immigrants themselves, maybe even recent immigrants, who are anti-immigrant. They think somehow they did it the “right way.” But it's fear, basically, I think.

Do you believe that there's a right way?

Well, I think that there should be a right way. I don't think chaos is good for anyone. Even the Catholic church doesn't teach open borders. I think having an organized system helps everybody because if not, people are unprotected and can be taken advantage of. The problem is, that what is established now as the “right way” is very impractical. It is very outdated. Even things like the CBP One app. I am a very good friend of mine in Tijuana, I just learned yesterday, that he was killed. We don’t know the details of what happened, but we hear stories like that all the time in Central America. If you have people coming to you and saying “If you don't cooperate in trafficking drugs, I’ll kill your son.” What are you gonna do? You are not going to say, “Kamala Harris says I shouldn't migrate, so maybe I should just stay here.” No, I mean, you're going to get up and go. The system is not in tune with the crisis.

A lot of the weight falls onto the Church. Onto you guys. Do you feel supported by the government at any level?

Well, I mean, you cannot talk about migration in El Paso without talking about Annunciation House and Ruben Garcia. He has been doing this for 46 years – this is his mission in life. He has a network of shelters, he has a couple of buildings, which have changed with time and he also has other churches that work with him. So, every day he gets a message from Border Patrol saying, we've processed, say, 600 people, and then Ruben Garcia sends them to different shelters, and the authorities themselves bus them to those locations. That's been the main support for asylum seekers. It is not just faith-based organizations, though there are a lot of churches, there is a whole network of nonprofit organizations.

And the city of El Paso has been kind of difficult in the sense that the support is sort of on and off. They have FEMA funds, so a year ago, they started renting hotel rooms. They would take people from our shelter who were sick, put them in a hotel, and monitor them. So, the city government has some facilities. They bought a school recently, an empty public school, and refurbished it to be a shelter, but it opened, and then it closed. So, we don’t know, but we are pushing them to move faster.

So the city comes to your shelter?

Yeah, they have vans, so they come around and we tell them who needs help and who needs to be taken. Sometimes people don’t want to go, but I think as it gets colder they will be more willing.

In general, it is sort of stressful because we don’t know how many people are going to show up. The other day we had 120, the day before 138, and before that 160. Our goal is somewhere between 120 and 130, but if it's cold, and if it's families with children, we will let in as many people as we can.

Yeah. How long do people tend to stay at your shelter?

It varies a lot. We don't have a deadline so after x number of days, you have to leave. We work with people. We've had people who already have arrangements with a sponsor or family member, and they'll say, "I'm leaving in a couple of days. I've got a ticket." Sometimes they will find labor for a day or two and then buy a bus ticket.

But we've also had families here for a long time. Like, the grandmother came with her grandson, but the mother of the child was not present. And so they separated the child. Finally, they were reunited, but there's some sort of immigration court hearing or something that is supposed to happen, so they're kind of waiting around.

Are most people waiting to hear about their asylum cases? What is the status of people who come through Sacred Heart?

Everybody that comes here has been processed by the authorities. When we first started, there were a lot of people who were undocumented, but now we only have people who are really in the process of seeking asylum, and their court date might be two years or a year.

The Venezuelans, in particular, don't have a lot of connections in the United States. So it's kind of a new group coming into the US. A lot of them don't have a stable sponsor or somebody who can take care of them. We've done a few, not many, but a few referrals to organizations or people that we know in other cities that will take families.

How have things changed throughout your time here?

When I was first here in, there were always a few people from Central America coming to the border. When I came back in 2016 it was clear that it was a very different reality. There were still people from Mexico coming, but it was this flow of people leaving Central America and even Cuba and some South American countries.

I have no doubt that the United States can take in millions of people. I mean, history shows other countries, poorer countries, doing this. It's not a matter of not having capacity. Of course, the US needs workers. These people from Venezuela come, some of them professionals, engineers, and, in general, people ready to work.

The problem, I think, is the system. And these, are bottlenecks or chokepoints at the border entrance. When you have 600 people being released in one day, that puts a lot of stress on the local community. It’s like a funnel.

A funnel at the top has a lot of room, but when it gets to the bottom, it's a crisis. And so the problem is, we're the funnel point here. And that creates what often the media portrays as this crisis.

If the US could somehow come up with a system to move people right away to other cities and process them there, so it doesn't become a burden on the local government and the local churches, there would be no major issue. People are needed to work. And these people want to work, I mean, I talk to them all the time, they want to work.

I think that's actually a really nice visual, the funnel.

Yeah, it's an international issue. You have people coming in from countries like Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Central America. All these people are entering the US, which is a huge country. We can handle that flow, but it has to go through these entry points. That's where the system becomes complicated. It becomes difficult.